REPORTING ON COASTAL RESILIENCE: A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR JOURNALISTS

As the world continues to heat up, the impact on coastal cities is increasing in both frequency and intensity. Without preparation, African cities are being hard hit, losing lives and livelihoods, eviscerating built and natural environments as well as economies.

We, as journalists, need to go past merely reporting on climate disasters when they hit. We need to help our audience better understand what makes cities vulnerable and what can be done to help them recover better from major climate events. This, at its core, is what coastal resilience is all about.

This guide was created by The Outlier for our journalist colleagues in other African countries, with a grant from the Earth Journalism Network and is based on our reporting of “A Perfect Storm”.

Our hope is that this will help our fellow journalists move swiftly through the basics of coastal resilience so they can report proactively, offering solutions on how we can all work on one of the most pressing issues of out time.

You can download a copy of this guide as a PDF here.

CONTENTS

- Resilience: A Definition in the content of the Global South

- Layers, Risk Factors and Data Points

- Where to Find Data

- Cost of the Climate Crisis

- Solutions

- Story Ideas

- Inspiring and Innovative Stories

- Resources

- Grants & Fellowships

RESILIENCE: A DEFINITION IN THE CONTEXT OF THE GLOBAL SOUTH

Durban’s 2017 Resilience Strategy refers to definitions of resilience as:

“The capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses, and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow, no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience…and the capability of a system to bounce back from a stress or a shock…and ‘bounce forward’ to a new and more resilient state.”

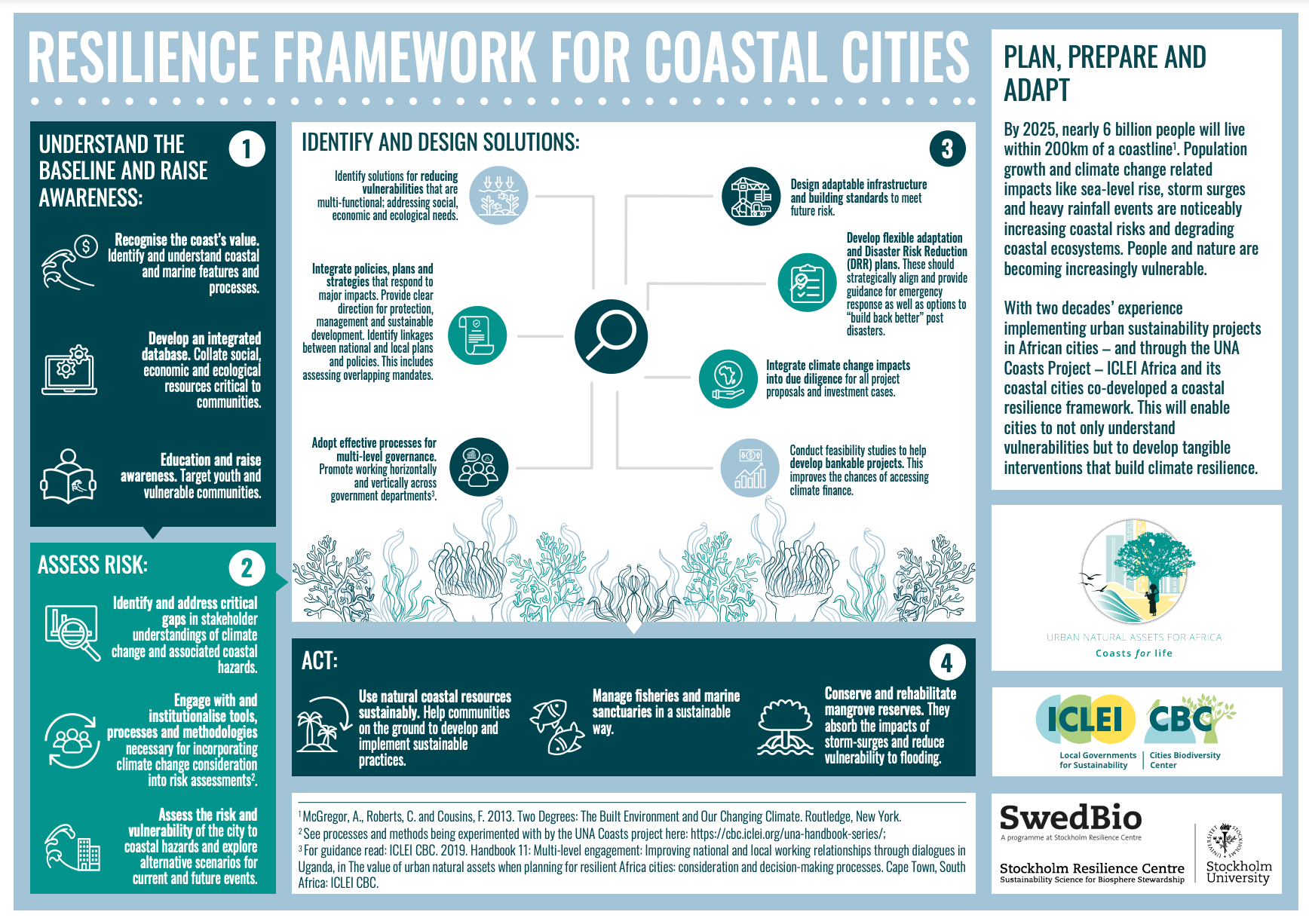

Coastal resilience, as defined by Coastal Resilience.org, an initiative led by the international environmental group The Nature Conservancy, is:

“About mitigating the vulnerability for human communities and natural resources simultaneously…[and] focuses on the resources at risk from coastal hazards including flooding and inundation and the options for protecting coastlines and people from these hazards, focusing particularly on natural solutions.”

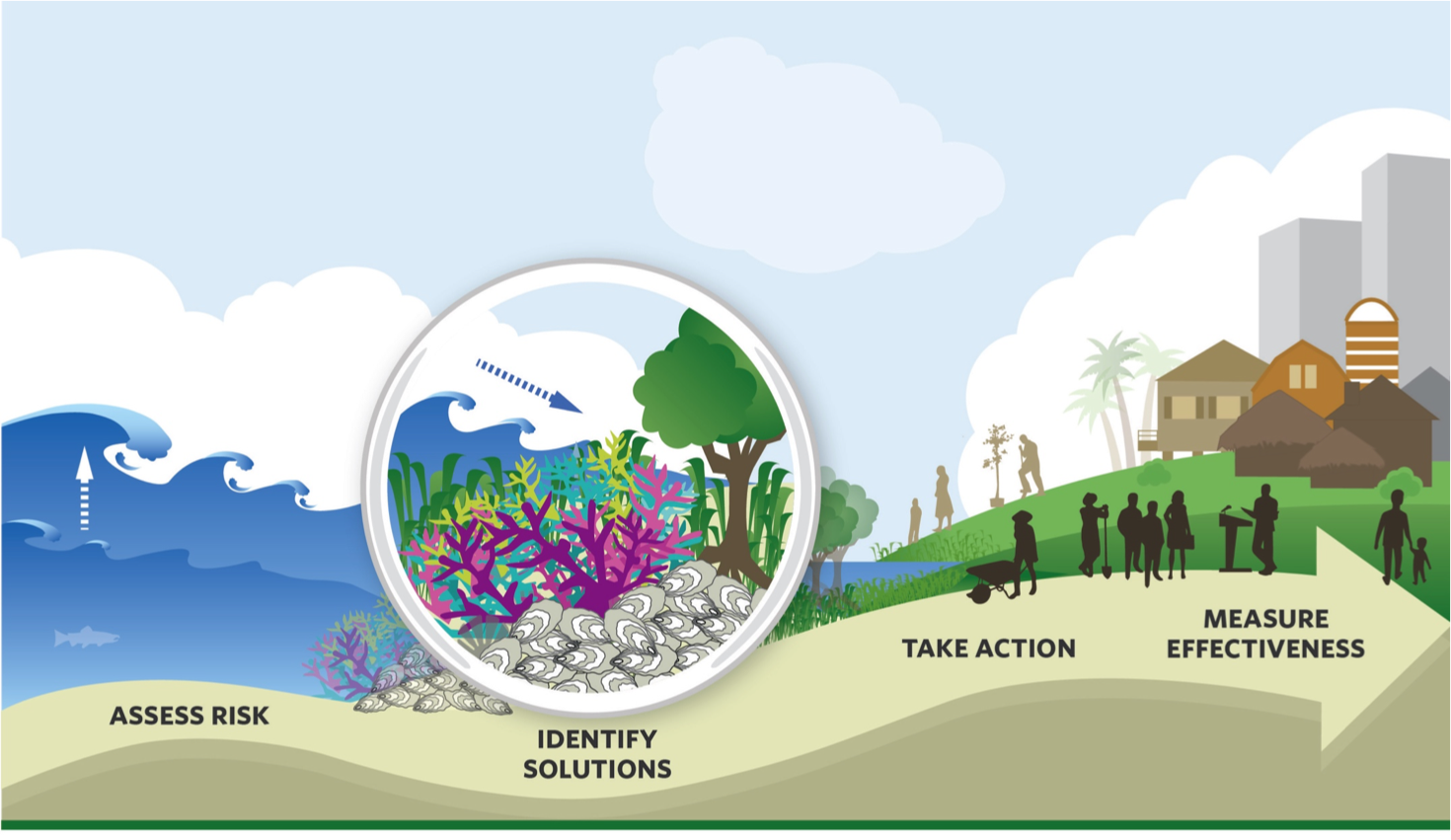

The approach begins with an assessment of the land, community and its hazards as a basis to plan mitigation and response. Mitigation aims to reduce harm from coastal hazards, and includes built and natural buffers and guiding urban development into the right places and out of the wrong places. Response includes dealing with the immediate emergency of the event as well as the reconstruction of the communities.

It is important to note that the April 2022 flooding in Durban was a case of inland river flooding, rather than a coastal storm surge; it was an extreme storm that brought high rainfall which caused rivers to burst their banks, and where a series of overlapping landscape and infrastructure issues made the damage worse.

This kind of inland flooding can happen in any city – even non-coastal cities – if they have similar river systems and development footprints.

A coastal storm surge happens when a severe weather system brings strong winds, and where nearshore ocean level rise drives extreme ocean wave impact. This kind of event can lead to a stretch of coastline flooding, rather than just flooding around the rivers and storm water drainage systems in parts of a city that are inland of the tideline.

That means a coastal city like Durban is at risk of a combination of both inland and coastal storm surge flooding during an extreme event, if conditions are right.

This US Climate Resilience Toolkit video is an easy-to-understand primer of the steps cities can take toward resilience.

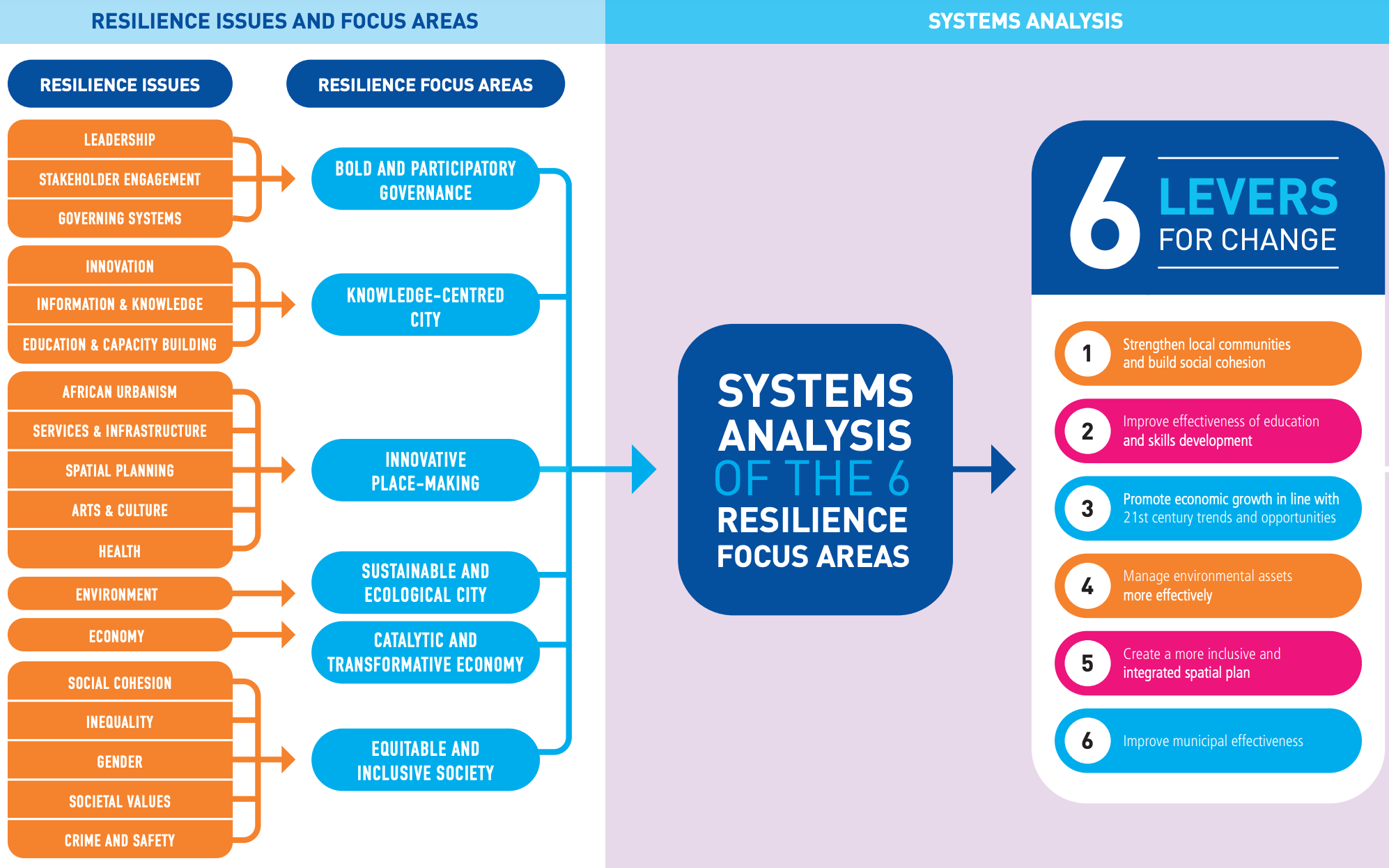

Because much of the theory and research about coastal resilience comes from the Global North, certain assumptions are baked into approaches that can be difficult to apply to cities in Africa and the Global South, according to the research team for Durban’s resilience strategy.

As part of the international Resilient Cities Network, Durban researchers pushed back on the sweeping approach for systemic and catalytic change, focusing their plans specifically on “collaborative informal settlement action” and “integrated and innovative planning at the interface between municipal and traditional government systems,” including secure institutional support for the process of integrating planning between municipal and traditional governance system

As the researchers pointed out:

“Our work tells a very particular story about what it means to be an African city in a rapidly urbanising world; constantly balancing issues of social vulnerability, informality, ecological degradation, politics and governance as local leaders try to determine the most appropriate and sustainable development path for the city.”

Development issues and other “non-climate stressors” have to be built into the first part of the assessment process, addressing issues including:

- economics, like rising prices;

- social issues, such as increasing crime or population growth;

- physical problems, such as ageing pipelines or poorly maintained sewers;

- political instability and corruption or regulatory barriers;

- and environmental issues such as pollution.

A World Resources Institute study on coastal resilience plans in Bangladesh, Colombia and the Philippines mirrors some of the African context, showing how a lack of interministerial coherence and co-ordination, fragmented information, competing priorities, and insufficient funding can affect planning and implementation.

A development first approach, which the Durban Resilience Strategy aligns with, means we need to consider “development priorities, current stressors, and vulnerabilities” before climate impacts in order to “understand current and future risks and identify priorities for action”.

LAYERS, RISK FACTORS AND DATA POINTS

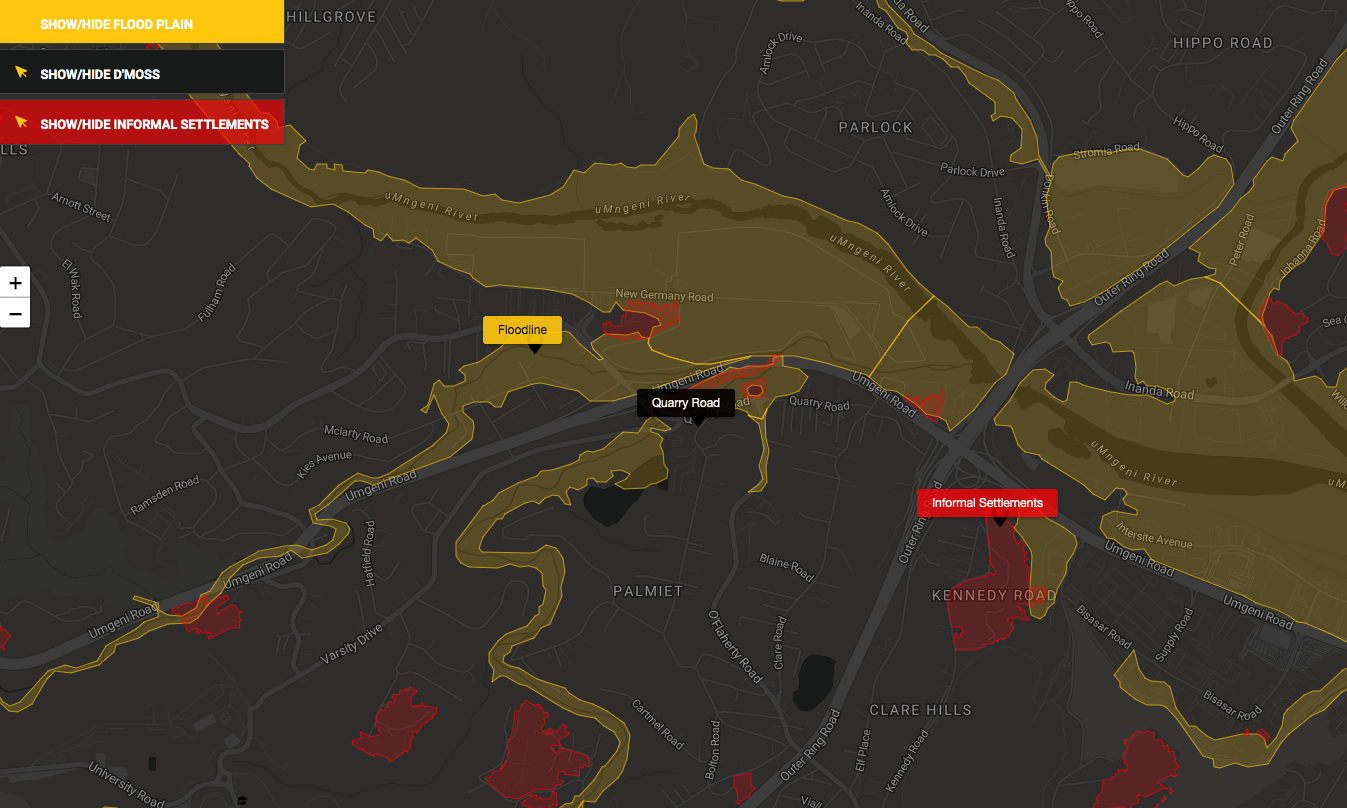

To understand the key risks and data points of coastal resilience, it helps to think in layers. Once you map each of the elements of a city, you can stack them on top of one another and get a better picture of vulnerable areas and problem spots.

Two visual interpretations that are useful in showing how layers can effectively communicate impact scenarios are:

- South Africa’s Coastal Viewer. This maps layers of vulnerabilities along the South African coast. Although it may be a little tricky to grasp, there’s a helpful video that explains the research behind it.

- An interactive map by the Southern Environmental Law Center in the US. It may not be relevant in terms of location, but its use of layers is designed to provide coastal residents information about what the future of their coast looks like.

Following are the risk factors and data points that scientists, researchers, urban planners and policymakers use to assess a community. These will differ depending on the specific environment. While not comprehensive, the list below includes the risk factors we identified in our research:

CLIMATE

From looking at past disasters, such as major storms, flooding and extreme weather events, scientists can see potential problem areas and try to estimate what, with the rapid changes in climate, is coming.

- Major flood timeline

- Historical rainfall

- Sea level rise

- Coastal storms

- Groundwater rise

POPULATION

Where do people live? Where are major population densities? Where do they shop, go to school, work, play? What are their demographics? The poor are far more at risk in disasters, as are women, children and the elderly.

- Population and population density. Where do people live now? What and where are forecasted growth areas?

- Demographics. Age, gender/sex and income are crucial aspects because these will highlight the most vulnerable populations.

- What are people’s livelihoods and how might they be tied to coastal life?

TOPOGRAPHY

This is the natural layout of the land, for example, the location of rivers, floodplains, slopes, etc.

- Hills, rivers, valleys

- Floodplains

- Coastal habitats

- Drainage systems

- Erosion points

INFRASTRUCTURE/BUILT ENVIRONMENT

It is important to map key infrastructure that supports the population and economy, such as water and sanitation systems, communications networks and the electrical grid, which may be disabled after a flood.

Mapping also needs to include systems essential for emergency response and recovery efforts during the disaster, such as hospitals, shelters, water filtration and toxic facilities such as refineries and chemical plants. If these are located in vulnerable areas, the ability of the population to bounce back will be reduced.

- Residential communities

- Commercial areas

- Retail centres

- Seawalls

- Dams

- Toxic keypoints

- Chemical plants

- Industrial areas

- Sewerage facilities

- Critical infrastructure

- Major buildings, including physical size and historical importance

- Government centres

- Communications facilities

- Defence and policing facilities

- Emergency services

- Shelters

- Energy

- Hospitals and healthcare

- Water and wastewater facilities

- Roadways

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC FACTORS

These factors merge with population data. In the African and Global South context, it includes a deep and wide understanding of key development issues and identification of vulnerable populations, such as women and children, people living with disabilities, or people living in informal settlements.

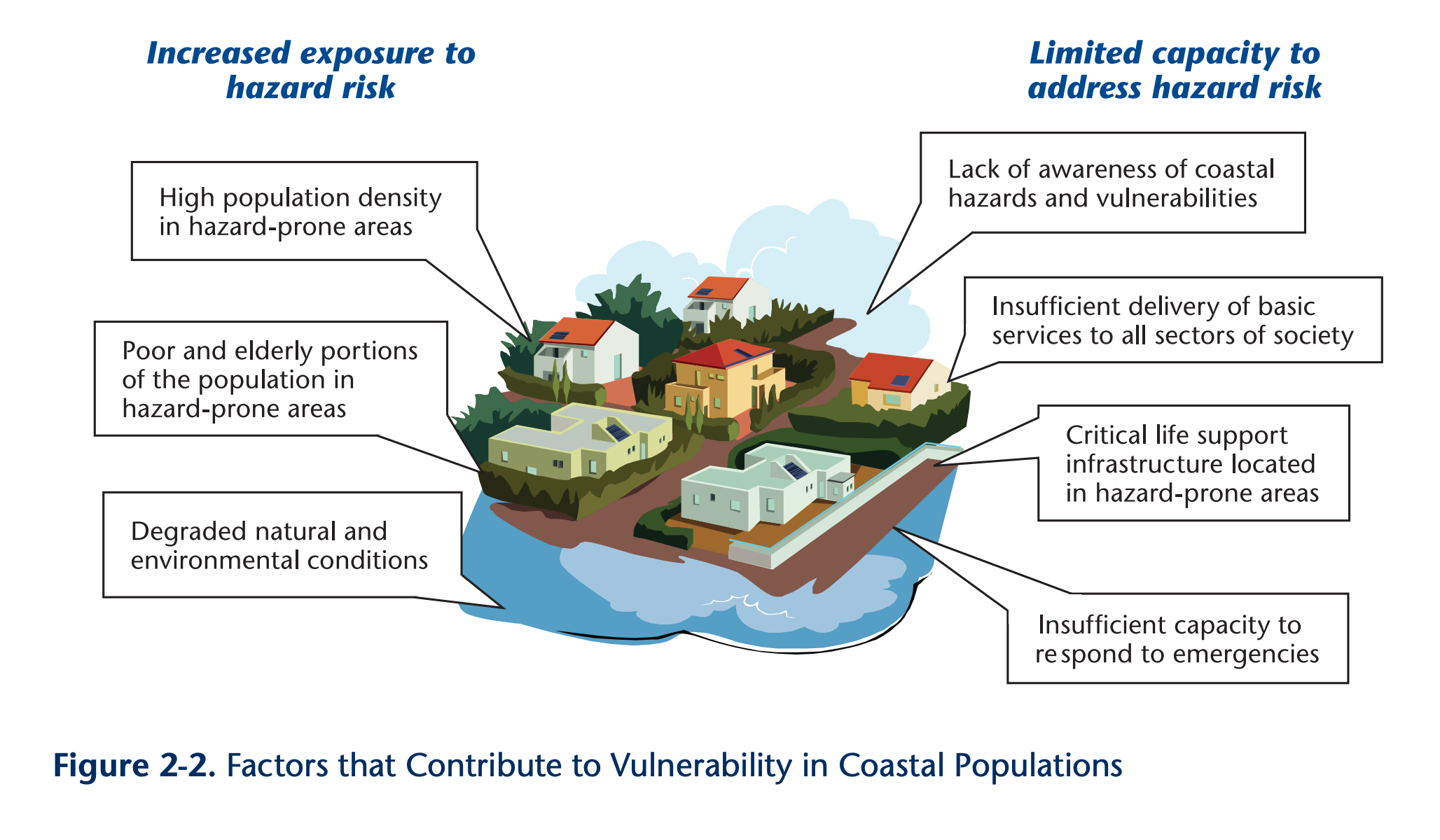

Social and economic factors play a huge role in the assessment and planning for mitigation and response in the Global South. A USAID guide for evaluating coastal community resilience notes:

“Changes in the economy and people’s quality of life are often the main criteria upon which a community’s resilience is judged after a disaster. The strength of the economy and the diversity of livelihoods greatly influence the community’s ability to prepare for disasters, quicken the recovery process, and adapt to changes that make them less vulnerable in the future.”

Alongside demographics, looking at other key social and economic issues – understanding key industries, the state of health centres, availability of humanitarian aid – are at the core of planning for coastal resilience, particularly in the Global South.

Basic development – including a lack of basic or poor infrastructure, such as buildings, roads, drainage systems and electricity; structural inequality such as apartheid spatial planning; political instability; or conflict. Other questions to ask include:

- How do population rise and migration issues influence the impact of climate events?

- What and where are the primary food sources and systems?

- What is the state of infrastructure in energy, transportation, communications, sewerage and water resources?

- Who will be impacted the most by extreme weather based on their location and their vulnerability?

WHERE TO FIND DATA

Climate change-related data sets about African countries are not particularly easy to find. Academic articles are a useful source of data, and often going through the reference lists of these articles will unearth links to other data sources. International agencies, such as the United Nations and the World Bank, have data portals with a range of development data, a few of which are listed in this section.

When it comes to illustrating climate change stories, maps are very important, so we’ll start there.

GEOGRAPHIC DATA

Maps are a useful way to identify and show where vulnerable communities are and the risks they face. To create custom maps, you need geographic data in the form of shapefiles (also known as SHP files) or geoJSON files. Those are the two file types most commonly used by data journalists. You will also need the GPS co-ordinates of specific places.

eThekwini Municipality has an Open GIS Data portal where the public can download a variety of maps in SHP and geoJSON formats.

If you can’t find an official data portal for the place you’re writing about, try a Google search, eg, Kenya maps shapefiles or Kenya maps geoJSON, to see if you can find a good source of map files for your country. You can also try searching on Humdata.org for map files of African countries.

There are a number of different tools you can use to make maps. The easiest for beginners is probably DataWrapper or Google MyMaps. But making custom maps often requires coding skills and the ability to work with a specialist mapping tool like QGIS.

Want to know more? The Outlier’s editor, Alastair Otter, put together a list of mapping tools for journalists.

CLIMATE, DEMOGRAPHIC AND DEVELOPMENT DATA

There are portals where you can access scientific data, such as Nasa’s Earth Data portal and the Copernicus Climate Data Store, but this data often requires specialist knowledge and programming skills to work with. You will need an expert to help you with these data sets.

The list below comprises data sets that can be downloaded in formats that can be opened in spreadsheets. Most do not require coding skills to download and analyse. They are relatively easy to understand, so journalists with data skills will be able to access them.

It is important to ensure you understand a data set before you use it. Read any background information and methodology and, if you are unsure of anything, ask an expert for help.

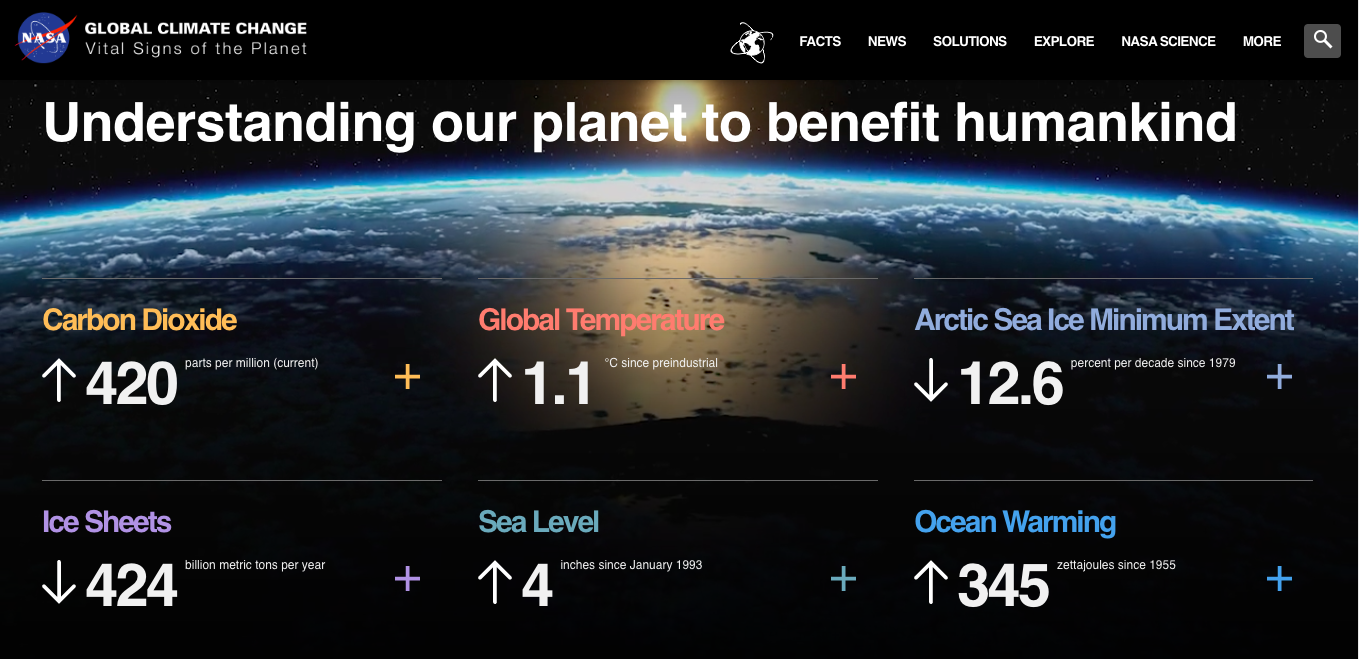

Nasa Global Climate Change Vital Signs of the Planet is a gentle introduction to Nasa’s data. It has global sea level, ocean warming, carbon dioxide and temperatures among others.

Our World in Data, CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions and more. This site is an extraordinary resource for global and country-level data sets and information on climate change-related issues. It is useful for journalists, not only because the data sets are open source (free to use) and downloadable, but also for the context it provides.

World Bank Climate Knowledge Portal. This is a useful, easy-to-access collection of historical and future rainfall and temperature data. It also includes country profiles of 20 African countries. It has downloadable data on South Africa to the provincial level.

IMF Climate Change Dashboard. This site has some interesting downloadable data for African countries on climate change and economics, such as fossil fuel subsidies, as well as temperature change and greenhouse gas emissions.

NOAA Climate.gov. The US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Agency has an interesting Global Climate Dashboard that’s worth exploring.

Edgar – Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research. This site has country-level data on a variety of air pollution emissions as well as greenhouse gases.

UN Food and Agriculture Organisation. This site has a range of country-level climate, food and agriculture-related data.

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Urbanisation Prospects. This site contains estimates and projections of urban and rural populations of all countries, as well as populations of major cities. It’s useful to see how populations are projected to rise in coastal cities.

Statistics South Africa is the official statistical body for the country so it’s the source of a wide range of demographic and other data, such as mid-year population estimates and unemployment data.

The Outlier has compiled a list of official statistical agencies in African countries.

The Em.dat International Disaster Database is a collection of data on natural disasters that have occurred around the world since the early 1900s. It includes African countries.

The South African Weather Service has climate and weather information for South Africa, mostly in the form of reports. There are no downloadable datasets on the site, but it is possible to request data. It’s worth finding out what data the weather service in your own country makes available.

The World Bank Open Data portal is worth exploring for a range of data sets relevant to coastal resilience and sustainable development.

The UNDP’s Human Development Data website has globally comparable data linked to the sustainable development goals.

The World Health Organisation’s data hub has a wide range of global health data.

Digital Earth Africa has a number of Earth observation data sets for the African continent. You will need some programming experience to access them.

If you’d like to learn how to use data in your storytelling and make effective data visualisations, The Outlier’s parent compnay, Media Hack Collective, offers training courses. Contact training@mediahack.co.za. The Outlier team also publishes how-to articles, such as how-to draw maps or scrape data from PDFs, on Inside Media Hack and Data Bites.

COST OF THE CLIMATE CRISIS

Over the past few years, millions of people have been displaced, thousands of homes have been lost and hundreds killed due to flooding across the continent. The US-government’s Africa Center notes that since the 1970s, Africa has experienced four times as many storms and twice the number of cyclones, with rain-related natural disasters growing 10 fold.

Indian Ocean cyclones are affecting large swathes of Africa’s east coast, moving past the historically-affected Madagascar and northern Mozambique, pushing up into Tanzania and down to South Africa.

The Nature Conservancy estimates global economic losses due to climate-related events over the last 50 years at $3.6-trillion. It estimates $1-trillion each year by 2050 because of rising seas and coastal storm surges in coastal communities, particularly urban areas.

A 2022 study by Deloitte predicts the globe’s soaring climate costs to result in a mind-numbing total economic hit of $178-trillion between 2021-2070.

In Africa, climate policies are estimated to lead to another number difficult to fathom: a 20% reduction in economic growth rates by 2050 and an average of 64% by 2100.

Economic factors highlighted in this coastal resilience case study in New York estimated some of the possible economic losses for disaster – buildings, relocation, income, shelter, vehicles, transportation and debris removal – and preventative cost outputs including capital, operating and maintenance costs.

The numbers and areas to cover are as big as they are fuzzy. But strategic social and economic input before disasters hit – and the inevitable output when they do hit – is integral to resilience planning on a national and local level.

The question for community leaders is where to put which resources first, weighing the vulnerability of economically disadvantaged communities most likely to be affected due to proximity, severity and potential of impact from specific climate-related threats, and the ability for the community to carry out actions that can prevent or allow for better bounce back post-disaster along with the cost-effectiveness of each.

Plans can include managed coastal retreat, reinforcing infrastructure, adapting storm water drains, implementing early warning systems and improving disaster management systems.

SOLUTIONS

Aside from the emergency response systems – which are normally built into local and regional planning – much of resilience planning is based around built and natural buffers.

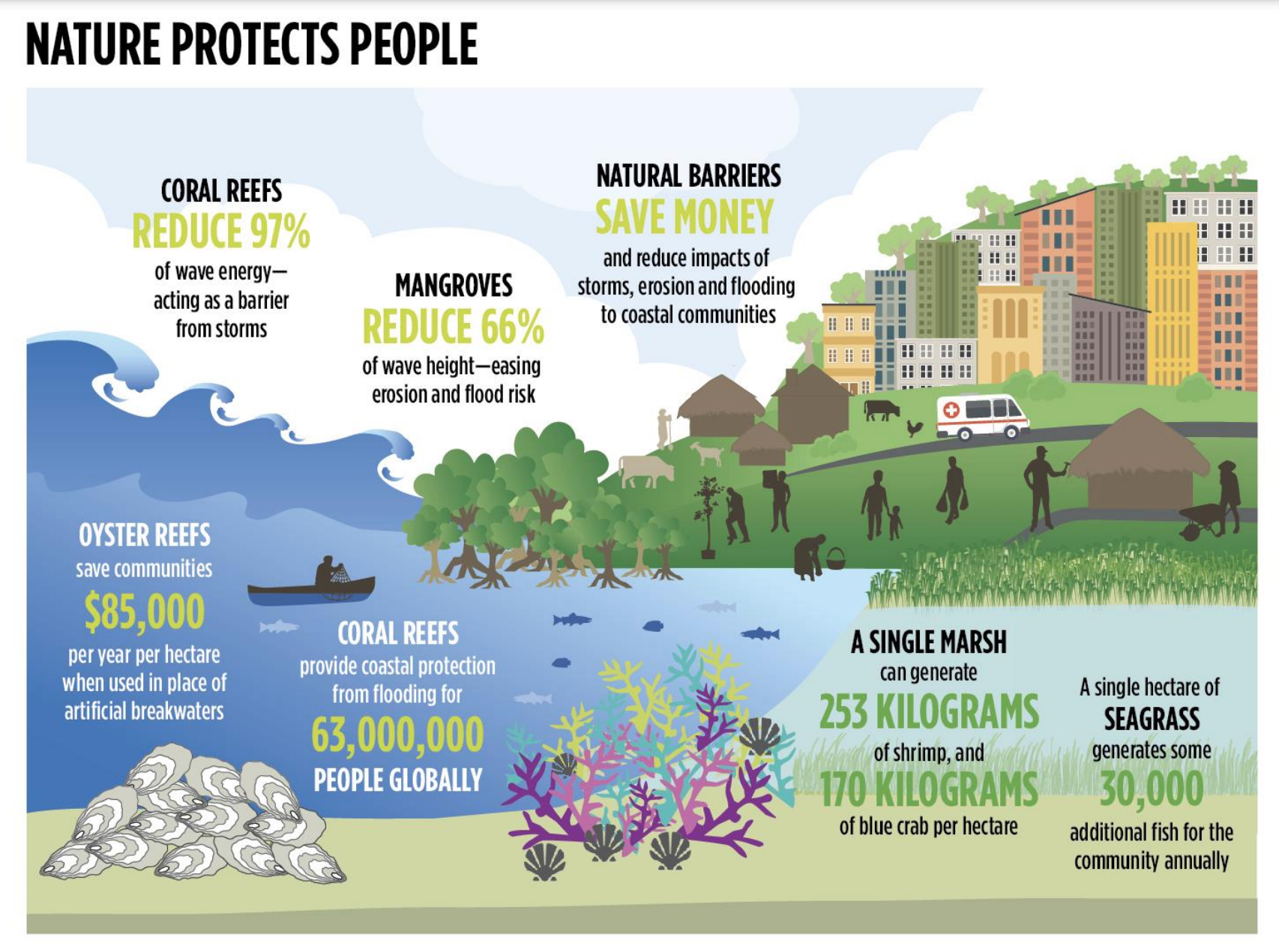

Built or man-made barriers include sea walls, dykes, levies and breakwaters. But scientists and urban planners are advocating for nature-based solutions or a hybrid system.

Check out this simple animation to get an idea of how nature-based solutions – which are cheaper to implement, more environmentally friendly and more malleable for future generations – can work when a storm hits the coast.

A WWF case study in Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa and Zambia on nature-based solutions found floodplains can reduce flood risk and regulate flows across wet and dry seasons. Mangroves and other coastal ecosystems play an important role in coastal protection.

The Blue Guide to Coastal Resilience and the Naturally Resilient Communities website illustrate nature-based solutions based on what the hazard is, such as coastal erosion or tidal or stormwater flooding. Although these are US- and Europe-focused, they are helpful resources.

STORY IDEAS

An essential part of climate change reporting is communicating stories in a way people can understand, breaking down complex concepts and science into understandable parts.

These stories also have to be easy for audiences to relate to and engage with – where people can see themselves or people they know. It also helps if stories offer solutions so people feel empowered, rather than reporting only on problems.

Solutions journalism isn’t reporting that glosses over problems but instead uses the same journalistic skills – a critical lens backed by in-depth, evidence-based reporting – to show examples of working solutions to development and climate challenges.

This type of reporting has been shown to give people a sense of agency in difficult situations, helping to overcome the sense of despair that might otherwise lead to inaction and paralysis. With a solutions-based approach, we can both keep the public informed and help catalyse opportunities for change.

Stories on coastal resilience don’t have to be sweeping. In fact, ongoing coverage is the best way to cover our coastal communities’ climate issues. Explainers can break down the science of erosion; graphics can show how sea level rise works or map natural buffers; profiles of scientists can show their work on innovative habitat conservation; talking to affected communities can help foster a better understanding of major local stressors; and following the money into coastal developments can ensure that these are done with resilience factors included – and properly spent.

Here are some story ideas to get you started:

What we learnt from the last storm: Many of the same communities have been hit with flooding and storms. Identify a community and see what individuals have learnt, and get advice for others for the future.

Defining the challenges: What are the different types of coastal city damage? Inland coastal flooding or tideline inundation? One happens when rivers burst their banks inland, the other from storm surges as the sea crashes in along beaches or river mouths. The differences can be nuanced, and the management and resilience responses are often different.

Getting technical: What is the climate risk profile of the city or community in focus? For instance, the CSIR’s GreenBook gives Durban’s current and future climate hazards, exposure, and vulnerability, and draws it together into climate risk zones. It also gives a climate actions tool which summarises each city’s strategies and plans

What’s the plan? Check out the building plans in the works in your community. Are they being done in risky areas? How do mitigation plans for coming climate changes fit into those?

Toxic key points: Show where chemical plants, oil refineries or factories sit along the coast to alert the community to potential dangers. (Check out this story for inspiration.)

Mapping the floodplains: Show where the most vulnerable communities are on a map. (Check out what we did here.. [link])

Eyes on the storm: Show where and how your city has been affected over the years to see patterns of vulnerable places as well as frequencies of severe climate events.

When disaster strikes: What do your city’s coastal climate disaster plans look like? How do the various city departments work together to support systems?

What you need to know to protect your home against floods: Ask the experts for advice on what you can do to prepare.

Protecting our coast: What are the natural and man-made buffers of our coast and how do they work?

Case studies: As our look into the Durban flooding shows[[[ link]]], case studies from recent climate events can shed light on what worked and what didn’t.

Indigenous knowledge systems: What can local communities teach urban planners, academics and policy makers about in mitigating climate change.

Advocating for climate policies: What are local communities doing to protect their environments?

City disaster management: Who is responsible in local government? What should communities expect? Are local authorities doing what they should, or what they promised? How effectively is the local government working with humanitarian aid and non-governmental organisations who offer support to communities during disasters?

INSPIRING AND INNOVATIVE STORIES

An impossible choice: When climate change arrives at your door, The Guardian, 15 October 2021

Climate change is stretching Mumbai to its limit, The Atlantic, 7 February 2022

Coastal cities face their mortality on climate ‘frontline’, AFP, 2022

Disappearing St Louis, NPR, 13 February 2023

Lament of the Brahmaputra riverbank, The Third Pole, 22 June 2021

Sea level rise could flood toxic sites along the Bay Area’s shore, San Francisco Chronicle, 7 December 2021

The beaches that are disappearing in Columbia, El Espectador, 15 January 2023

The coming California megastorm, New York Times, 12 August 2022

Vanishing land: Climate change displaces Black families along Gullah-Geechee corridor, Post and Courier, 26 November 2022

We don’t have the power to fight it, Scene On Radio, 2 November 2021

Your sea wall won’t save you: Negotiating rhetorics and imaginaries of climate resilience, Places, March 2018

RESOURCES

In addition to the links throughout the guide, here is a brief list of some of the best resources we found about understanding coastal resilience.

GreenBook: Adapting Settlements for the Future An online tool compiled by the CSIR to help South African cities with climate resilient development planning.

Bangladesh: Enhancing Coastal Resilience in a Changing Climate This World Bank-sponsored study reviewed progress in Bangladesh and maps a way forward.

EJN’s Tipsheet for Investigating Coastal Resilience The Earth Journalism Network’s guide for journalists from around the world, based on two webinars.

EJN’s Covering Coastal Resilience Projects Stories on climate resilience supported by the Earth Journalism Network.

How Resilient Is Your Coastal Community? A Guide for Evaluating Coastal Community Resilience to Tsunamis and Other Hazards This USAID guide is based on what was learnt from the 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean.

How to adapt your city to sea level rise and coastal flooding and How to reduce flood risk in your city Two succinct and resource-heavy articles from C40, a global network of cities working on the climate crisis.

The Blue Guide to Coastal Resilience A nature-based solutions guide from The Nature Conservancy, a global environmental nonprofit which has done extensive work on the issue.

The Conversation Africa’s brief, accessible analyses from academics cover topics such as African coastal disasters, storms and flooding issues. This is also an excellent resource when looking for regional experts or story ideas.

US Climate Resilience Toolkit While built for US communities, there are some helpful basic theories, interesting case studies and resources.

GIJN’s Guide to Sea Level Rise The Global Investigative Journalism Network guide is dedicated entirely to sea level rise, a key coastal resilience issue.]

GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS

The following are a list of grants and fellowships for journalists working on climate change stories in Southern Africa.

- Earth Journalism Network

- GRID Arendal

- Henry Nxumalo Foundation

- International Women’s Media Foundation

- Mongabay

- Pulitzer Center

- Dag Hammarskjöld Fund for Journalists

This resource for journalists was written by Tanya Pampalone, Laura Grant and Leonie Joubert for The Outlier, a publication of Media Hack Collective, March 2023. It was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

Email us at climate@theoutlier.co.za if you have any comments or suggestions to help us improve this guide.