A Perfect Storm

Don’t go to sleep. The river is rising. There’s more rain on the way. Be ready to evacuate.

Families living along this stretch of one of Durban’s 18 major rivers believe it was this warning that spared them any deaths by drowning, when floodwaters tore many of their makeshift board-and-tin homes apart.

But on 11 April 2022, a worst-case scenario was nevertheless unfolding.

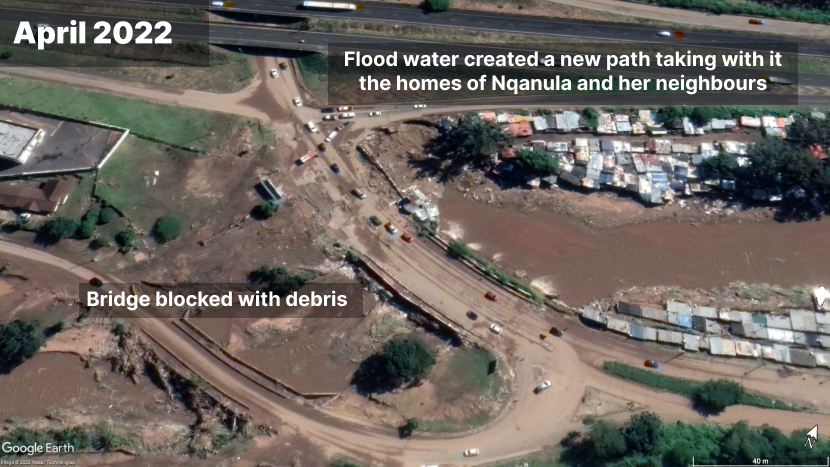

Community leader Nomandla Nqanula had eyes on a nearby bridge. She snapped a photo and fired it off to the city’s disaster management team, showing that tree debris and other flotsam was snarled up against it, trapping the water’s escape. A short while later the final instruction came through from the disaster unit. It was time to get to higher ground.

It was like a disaster movie, Nqanula says, with containers from nearby shops caught in the current and slamming into dwellings. Then there was the final terrifying escape as she and her neighbours formed a human chain to cross the nearby M19 highway which was disappearing under the fast-flowing water.

When the sun rose on Tuesday, there was nothing but a hole gouged into the bank where Nqanula’s home had stood. Like many, everything she owned had been washed away. Their lives, at least, had been spared.

Other communities in the eThekwini municipality on South Africa’s east coast, more commonly known as the city of Durban, weren’t so lucky.

By the time President Cyril Ramaphosa called a state of emergency on April 19, at least 435 people were dead and 54 were missing. Thousands had lost their homes and businesses. Roads and bridges were torn away, communications knocked out, sewerage works gutted, and water infrastructure and power grids destroyed.

The initial damage was estimated at R17-billion, although the final bill might run even higher than R25-billion, eThekwini’s senior manager in the climate protection branch, Dr Sean O’Donoghue, said in a webinar a month after the disaster.

It was the perfect storm: not just the weather system, but the physical shape of the city it hit. Durban is a complicated sprawl of old settlements and new; concrete-and-steel standing alongside shantytowns; where infrastructure and service delivery are steps behind the needs of its fast-growing population; where hilly terrain is shot through with boom-and-bust rivers.

No coastal city – no matter how developed – will escape the extreme events coming with global heating. While Global South cities are uniquely vulnerable, insights from the storms that brought severe inland river flooding in Durban in April 2022 shows how they can brace for future impacts.

Early Warning

Resilience is the ability to bounce back after a shock like this, be it a community, person, or system.

That night at Quarry Road, the city was piloting a novel approach to its existing early warning system that, if it worked, could help other flood-exposed communities not only survive these inevitable and escalating events, but recover better.

But the first red flag of what was to come arrived months before the April storm.

The South African Weather Service warned that the ongoing La Niña weather cycle — a years-long natural event which brings higher-than-average rainfall to South Africa — had waterlogged the soils ahead of the 2022 rainy season. The saturated ground wouldn’t be able to hold much more water, increasing the likelihood of flooding.

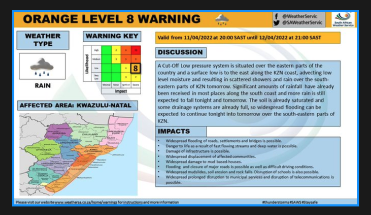

Then, on 10 April, the Weather Service issued a Level 9 weather warning on its 1-to-10 alert system. It had only issued a Level 10 warning once before, in January 2021 when tropical storm Eloise landed on South Africa’s coast, affecting neighbouring countries, and hitting Mozambique particularly hard.

The short-range forecast that April predicted a cut-off low, which would bring a high chance of dangerous flooding, kicked eThekwini’s Disaster Management and Emergency Control Unit’s protocols into play.

In Quarry Road, the community-based early warning system that was in the making for eight years was now being tested in real time. This meant marrying the city-wide forecast with the fine-grained details of the catchment that feeds into the Palmiet River.

Information began flying across a digital group chat platform that allowed the various parties — the city’s disaster management unit, the city’s senior climate scientist, a university academic who helped design the system, and volunteers within the community — to stay in touch.

The city’s catchment manager began monitoring the rain gauge upriver of Quarry Road, knowing from hydrology models that it would take 40 minutes for water to travel from there to the Quarry Road community.

The water had already risen to a dangerous two metres and more was on the way.

When Nqanula reported the bridge blockage, the disaster team escalated the response. Time to evacuate.

It was 11pm. She had just enough time to grab her identity document and cellphone.

The system, says University of KwaZulu Natal’s School of Built Environment and Development Studies geographer Catherine Sutherland, who is part of the system’s design and piloting, is novel in a few ways.

Rather than relying only on a blunt catchment-wide weather forecast, this zooms in on local-scale conditions and real-time data. It uses the SA Weather Service’s new impact-based weather alert system which goes beyond simply giving the details of how much rain might fall, or what wind speeds to expect, but flags the likely damage these might cause to the built environment, explains chief forecaster Kevin Rae.

It then draws on individuals in the affected community to get the most complete picture of the event as it unfolds.

This kind of early warning system is just one lever in the complicated machinery of a city system in an emergency situation like this, and a good example of how it can build better resilience.

Portrait of a coastal city

Durban’s 2022 storm was extreme, but not unprecedented. Parts of the city were uniquely exposed because of features of its built environment and the human systems that run it. The natural landscape on which these are built played a role, as did the social and economic context in which people live, and the people themselves.

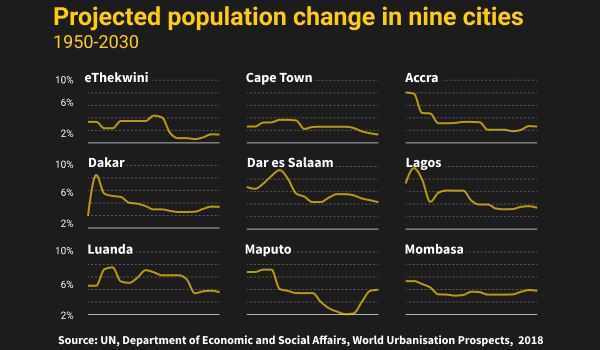

Durban is the country’s third-largest city, with a population of 3.9-million and climbing as more people are drawn from the countryside in search of a better life. The city has many well-established suburbs, but it also has a housing backlog of 387,000 units for those who can’t get into the formal property market. About a quarter of Durban’s residents are in informal settlements, meaning some 300,000 households live in makeshift dwellings in neighbourhoods where the city struggles to keep up with service delivery demands such as water reticulation, sanitation, storm water systems, electricity provision, and garbage removal. Where these fail, a community is more at risk of flooding during a storm.

As climate impacts escalate, they will do so into this context.

Climate analysts say global heating contributed significantly to the April storm’s severity. A storm of this scale would normally happen about every 40 years, according to a report by the World Weather Attribution initiative that quantified the link between this event and human-caused carbon pollution. But with current levels of warming — already up by 1.2°C relative to pre-industrial conditions — it is more likely to be a one-in-20 year event. But as global heating speeds up, an event of this magnitude will come around even more often.

Durban needs to focus on two things to ready itself for this inevitable future, says a team of South Africa’s leading climate scientists and researchers, writing for the Institute for Security Studies in May 2022.

First, it needs effective early warning systems in the run-up to disasters. The one trialed with Quarry Road is a case in point.

Second, it needs to address the kind of systemic problems that shape the city’s built environment. This includes the many forces that lead to people building informal homes on the banks of a flood-prone river in the first place.

Quarry Road is one of more than 580 informal settlements in the eThekwini Metro Municipality.

About 300,000 households or about a quarter of the city’s population live in these settlements.

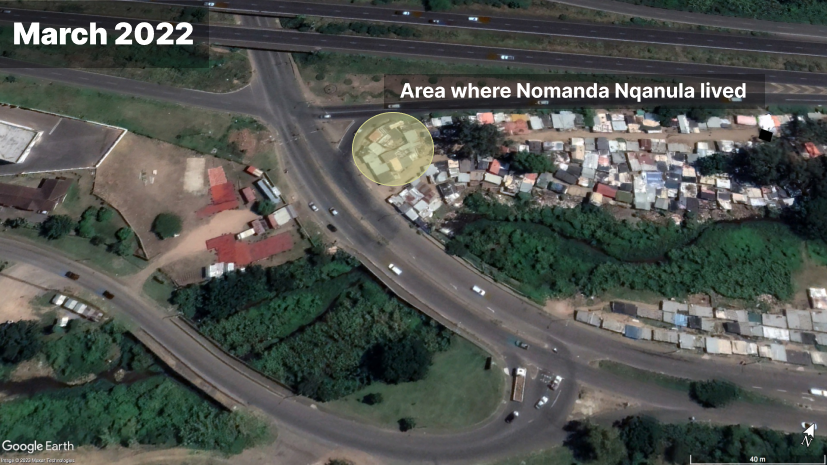

Quarry Road was established in the 1980s. It lies on either side of the Palmiet River, sandwiched between the M19 highway and Quarry Road.

It lies in the 100-year flood zone of the Palmiet River. Researchers describe it as one of the most risk-prone settlements in Durban. The river flooded in 2016, 2019 and 2022.

Despite the flood risk, the settlement continues to grow.

In 2019, researchers estimated that there were 1,030 households, or about 3,000 people, living in Quarry Road.

Many of Durban’s informal settlements are in flood risk areas, so they are particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events.

Bridge over troubled waters

Nqanula thought her house would be safe — it was further from the water’s edge than many others, tucked up against the road on higher ground. But when the torrent needed a new path to the sea, it tore around the bridge, directly through the cluster of homes where she lived.

The very structure that was built to allow the river to flow while letting the city tick over around it — and which some Quarry Road families had even built their dwellings under — became the very thing that turned the water into a destroyer.

The built environment increases flood risk, and at the same time is more likely to be destroyed by the force of that very water.

The location of houses, roads, industrial sites, malls, bridges, utility stations, and so forth change how rainwater moves through the landscape. When heavy rains hit the natural environment, vegetation, roots, and earth help it seep into the ground, slowing its release into rivers and out to sea. Once the land is capped over with an impervious shell of concrete, asphalt, paving, buildings and structures like bridges, the natural brakes are gone. Even with well-considered storm water drainage, the volume and speed of runoff gets turbo-changed.

A city faces the almost impossible task of managing its inherited built environment, with the needs of its fast-growing footprint. It then has the responsibility to climate-proof both.

To do so, Durban needs to identify hazard-exposed land, and stop development in these zones, warn the climate scientists in ISS Today. Local government needs to take charge of all developments — even informal sprawl — by limiting it to safe areas. It needs to consult communities in high-risk areas, like those in Quarry Road, and help them move to safer settlements, which the city will need to build. Exposed infrastructure needs flood protection and new infrastructure should be planned, designed, and built with extreme flooding in mind.

The city knows this, and outlines its plans in various policy documents, such as its climate change and resilience strategies. For instance, it plans to upgrade 80% of drainage infrastructure by 2030, and 100% of it by 2050. Durban hopes to restore 7,400km of river corridors to be ‘clean, safe, healthy, and climate resilient’ by mid-century.

Rolling this out, though, happens within the limitations of tight budgets, contested political interests, institutional capacity, and the ongoing housing and service delivery backlogs in a city whose population keeps growing.

The 100-year floodline

South Africa's National Water Act stipulates that information about floods and potential risks must be made available to the public. Maps showing the 100-year floodline are a way to do this. However, the name is a bit misleading. A 100-year flood is one so severe that it has only a 1% chance of happening in any given year. It doesn’t mean that such a flood will only happen once every 100 years.

The map below shows the 100-year floodlines of eThekwini’s rivers and where the city’s informal settlements are as well as the areas that form part of the Durban Metropolitan Open Space System (D’MOSS). These are open spaces in public, private and traditional authority areas intended to protect biodiversity and ecosystem services. They include nature reserves, large rural landscapes in the upper catchments and riverine and coastal corridors, grasslands, forests and wetlands.

Palmiet River

The splintered trees and solid waste that dammed the Quarry Road bridge was not an isolated incident. Culvert blockages like this are common here, forcing rivers to break their banks and gut surrounding infrastructure.

Durban is a diverse natural landscape, its steep rolling hills broken by winding river valleys which slump to a coastal plain. It is in the wettest and most humid part of the country, getting over 1,000mm of rain in summer. Its 7,400km of streams and rivers, running through 18 catchments, are heavily damaged by urban sprawl: solid waste dumping; leaks from sewerage works and pipes; industrial pollution; sand mining; and invasive alien plants.

Heavy rainfall brings more water into a river system, flowing faster, because of the hard surfaces of the altered landscape, and the rivers clogged with alien plants and litter, storm water drainage systems and river culverts block easily, and often.

Understanding that healthy rivers and wetlands are essential to flood-proof a city, the municipality plans to roll out a community-based river restoration project, which draws on a project that’s been piloted across 300 km of river in parts of Umlazi, Inanda, Ntuzuma, and KwaMash, all less developed neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the city. The Sihlanzimvelo programme is run by the city and draws on locals, assigning groups of up to eight people to tend to their own 5km stretch of river where they clear overgrown plants, collect litter, report pollution, and repair eroded banks.

O’Donoghue, from eThekwini’s climate protection branch, says the plan is to scale this up, city-wide. By his estimates, an investment of R7.5-billion in river restoration over two decades will prevent R1.9-billion in infrastructure damage caused by culvert blockages alone. But, he says, it could also create upward of 9,000 jobs.

A restoration project like this, applied to a river system like the Palmiet, would give a natural ‘airbag’ that would protect Quarry Road from the kind of weather shock that washed away 400 homes in the settlement in April.

The Palmiet Nature Reserve is just 15 minutes’ drive inland of Quarry Road. It is 90 hectares of relatively unspoiled forests, meandering rivers that tumble over waterfalls, and grasslands higher up. A nature reserve might seem like a luxury in a city that needs land urgently for new housing. But a recent study into the value of Durban’s natural spaces — rivers, wetlands, forests, soils, and the like — estimates that its rivers give a water flow regulation service valued at R29.5-million annually.

Protecting unspoiled ecosystems and green belts — even altered ones — doesn’t just give people a beautiful place to relax and play. They give a suite of “ecosystem services” that absorb extreme weather shocks. Plants, trees in particular, are natural air conditioners that offset the urban heat island effect, which will make heat waves more lethal. Healthy wetlands and rivers — the vegetation around them, and their soil — smooth out the release of rain water into rivers, which reduces flooding, erosion, and river siltation. Dunes, estuaries, and mangroves soften the force of ocean surges during storms, buffering against erosion and wave damage to infrastructure.

Best laid plans

To flood-proof a city, particularly the third of its residents living in informal neighbourhoods like Quarry Road, a city needs a plan.

On paper, Durban has one. The 2019 Climate Action Plan lists what’s needed to tackle the flooding problem: an early warning system; the one-in-100 year floodline map that, when drawn together with climate projections, allows for better planning and management in flood-risk areas; and the many state partnerships necessary to restore and conserve ecological infrastructure.

The intention is to limit and discourage development in flood risk areas, and protect existing infrastructure from flood risk. It lists the actions necessary to keep river corridors healthy, and keep the ecological infrastructure working.

Elsewhere, the plan flags the need to move communities out of flood-risk areas and house them appropriately in properly-serviced areas.

This document dovetails with the city’s many other plans and policies, such as the 2017 resilience strategy, its spatial development framework, and the integrated development plan, a complex negotiation which needs to align with various other local, provincial, and national government laws and constitutional obligations.

Dr Debra Roberts, a leading South African climate and urban biodiversity scientist working in eThekwini, is the city’s chief resilience officer and helps coordinate resilience and sustainability “workstreams” across the municipality. O’Donoghue, meanwhile, oversees the city’s climate adaptation response. The city also has a senior climate scientist, Smiso Bhengu, within its ranks. Their expertise, and the positions they hold within the city institution, allow them to link different government departments whose responsibilities overlap around resilience or climate-focused initiatives. It also helps the municipality coordinate with non-state bodies, such as academics, civil society, and the private sector, to rally around shared-partnership initiatives.

The Palmiet Catchment Rehabilitation Project is one such project, and an example of how climate literacy within a city’s administration — and the resulting planning and institutional arrangements — makes it into the real world. This project is geared towards addressing flood risk along the catchment, and specifically for the Quarry Road community, using social, governance, and environmental levers. It draws in city personnel, university researchers, and the local community. The community-based early warning system that saved many lives on the night of 11 April is one cog in the wheel of this complex machinery.

Sea Level Rise

The April 2022 flooding in Durban was a case of inland river flooding, rather than a coastal storm surge. An extreme storm brought high rainfall which caused rivers to burst their banks, and a series of overlapping landscape and infrastructure issues made the damage worse. This kind of inland flooding can happen in any city – even non-coastal cities – if they have similar river systems and development footprints.

A coastal storm surge happens when a severe weather system brings strong winds, and where nearshore ocean level rise (caused by low air pressure) drives extreme wave impact. This kind of event can lead to an entire stretch of coastline being flooded, rather than just flooding around the rivers and storm water drainage systems.

A coastal city like Durban is at risk of a combination of both inland and coastal storm surge flooding during an extreme event, if conditions are right.

Floods caused by heavy rainfall are the most common extreme weather events experienced by eThekwini. But coastal storms are expected to increase in frequency and intensity, putting low-lying areas of the city near the shoreline at risk of flooding and erosion by pounding waves.

Tidal records collected near Durban harbour since 1970 show sea-level has increased by 2.7mm a year. Scientists project that the level of the sea could rise by between 0.3m and 1m by 2100.

Using data derived from satellite imagery, Digital Earth Africa has mapped the median position each year of the shoreline along the eThekwini coast from 2000 to 2022. The area around the mouth of the Umgeni river is marked as an area of coastal retreat. Move around the map to explore other parts of the eThekwini coastline.

Most coastal cities will need to plan for a managed retreat as sea levels rise and more potent storms bring damaging ocean surges. One way to do this is through a set-back line, a mapping process that shows how far inland the tide will move in specific parts of a coastal city over different time frames and under varying climate scenarios. Cape Town is working on its policy-embedded set-back line and Durban’s planning documents include this process too.

The CSIR has developed an online coastal flood hazard assessment tool, to help cities anticipate and plan their moving tidelines.

Sweet for some

That April, about 20km uphill of Quarry Road, at the newly minted Cornubia business-industrial-residential park, an emergency of a different kind was unfolding.

A temporary pollution holding dam, built a year earlier to capture the toxic runoff from a fire that destroyed a warehouse filled with agri-chemicals and poisons, was flooding. A cocktail of heavy metals, carcinogens and pesticides was spilling into the Ohlanga River, killing vegetation and fish, and forcing the city to consider closing the beaches at the river mouth.

It will take years to fully understand the health and environmental fallout, environmental justice activists warn, but the impact on property prices and the city’s housing plans is likely to be swifter.

The April floods destroyed 13,500 homes across Durban, a third of which were in informal settlements, and the city had to shelter 7,245 people in halls and care centres immediately after the event. By December, many were still homeless.

After a disaster like this, the city has to help families rebuild their homes, or place them in state-subsidised housing, which means fast-tracking developments to meet the existing housing backlog.

The farmland surrounding Cornubia, much of which is owned by the sugarcane conglomerate Tongaat Hulett, is earmarked for some of this development.

Activists worry that history will repeat itself here: that the contaminated land, some of which falls into Cornubia’s mixed-income housing plan but may no longer be appealing to private property buyers, could be offloaded onto government at a bargain-basement price, and used to relocate flood evacuees like those from Quarry Road.

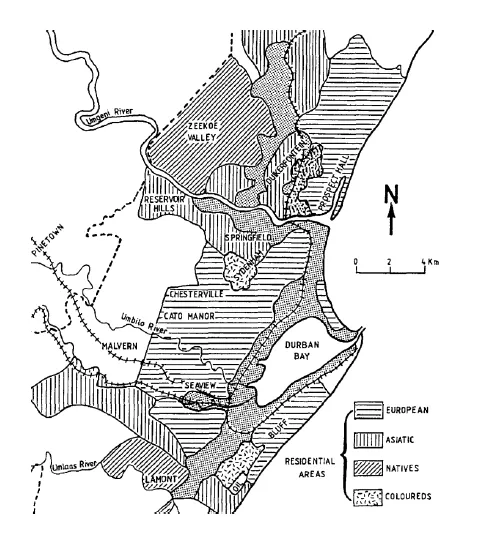

South Africa’s apartheid-era laws split the city along race lines — a proxy for class — leaving cities with a spatial divide that haunts them to this day. The 1958 Group Areas Act pushed poorer people of colour into Durban’s most marginal and often flood-prone areas. Three decades after these laws were dismantled, Durban’s residential divide is largely unchanged.

Where law once segregated the city, locking in a spatial divide between rich and poor, now the private property market maintains it.

Environmental racism isn’t unique to South Africa. Around the world, poor communities of colour tend to wash up in the most environmentally marginal, degraded and polluted parts of many cities.

Cornubia is a public-private partnership between Tongaat Hulett and the eThekwini municipality, and is billed as one of the “catalytic projects” that will help meet the region’s growth and development goals.

It will include a new city centre, a fresh start now that Durban’s aging central business district (CBD) has lost its shine, falling into disrepair following municipal neglect and investor flight, much as Sandton replaced Johannesburg’s neglected CBD.

But environmental and planning lawyer Jeremy Ridl warns that the corporation’s power as a profit-motivated landowner and developer has allowed it to steer Durban’s spatial planning in its own interests.

Ridl is heading a coalition of affected communities and civil society working with government and private agri-chemical firm United Phosphorus Limited (UPL), that owned the destroyed warehouse, to ensure transparency and accountability in the post-fire mop-up. He flags Cornubia, and the pollution bedeviling the site, as an example of how the private sector and the free market maintain Durban’s inherited inequality gap and the environmental racism that plagues it. This distorted power relationship can undermine even the most competent city officials, institutions and policies.

Many of Durban’s development challenges, which apartheid played a significant role in creating, come together with fast-paced urbanisation, free market economics, and the climate crisis to create a perfect storm that threatens resilience, writes Roberts in a co-authored report on the city’s resilience strategy journey.

Meanwhile, the health and environmental issues following the chemical warehouse fire at Cornubia seem far from resolved. Environmental journalist Tony Carnie’s December 2022 reporting in the Daily Maverick showed that the ground beneath the damaged warehouse contains dangerously high levels of pesticides, carcinogens, and heavy metals and there's a risk these toxins could make their way into the groundwater.

These findings are a reminder of the need for rigorous ongoing monitoring at the site, and transparency in management and further development in the contamination zone.

Building back

When the flood took Nqanula’s house, it took everything. She was left with nothing but the sodden clothes she spent the night in, huddled on that service station forecourt waiting out the storm.

It took her independence, too, she says; her confidence, her happiness.

Someone brought blankets and soup the next day, but Nqanula remembers that emergency vehicles couldn’t get in at first because the roads and bridges were so badly damaged. On the second night, they slept on the floor at a nearby school, until they were moved to another hall. Eight months later, many of the Quarry Road evacuees were still living in care centres and relying on the city or its civil society partners for food and other provisions.

Nqanula decided she’d rather find somewhere to rent. She needed space to heal, to pray, to “have herself back”, away from the traumatised crowd.

This isn't the first time she’s had to put her life back together since she moved to Quarry Road in 2013 — new clothing, new furniture, new bed, everything. In 2019, a flood destroyed her house, but she wanted to stay in the community so she bought a shack on the other side of the river. It was higher up, further from the water.

In her early years in Quarry Road, Nqanula’s two sisters lived with her. But between them they decided to spread the risk. Informal homes are easily damaged by flood or fire. If they lived between two homes, should one be destroyed, they’d have a backup, so one sister moved to Glenwood, about 8 km away. After the April floods, Nqanula sent her younger sister there, while she rented a place a 15-minute walk from her old home.

People settle in flood-exposed places for many reasons: they want to be close to jobs and the other opportunities that come with being close to the heart of a bustling city, even if they understand there might be weather-related risks. None can afford a suburban house, and the waiting list for a state-subsidised house is endless. Some build their homes on a site that looks ideal during the dry season, unaware of what will come with the rains. Many also have a strong connection with their community, and don't want it torn apart in a relocation process.

Quarry Road is flagged as a priority for relocation to a safer, properly-serviced site. But it’s a slow process and needs community buy-in. In the meantime, the city is trying to improve basic services — an “in-situ upgrade”, they call it — with better garbage removal, communal water taps, pit toilets and ablution blocks, and stormwater management. Flood-proofing a community is, afterall, about more than just putting a solid roof over someone’s head. Homes need to be in a neighbourhood with working stormwater drains, refuse removal, water reticulation, and the lights on.

Until then, many from Quarry Road are stuck in limbo.

If Nqanula could ask for one thing, it’s that the municipality could give all of them a piece of land “away from the water”. They can build their own homes, she says, even if it takes a long time.

Just a small, safe piece of land.